- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

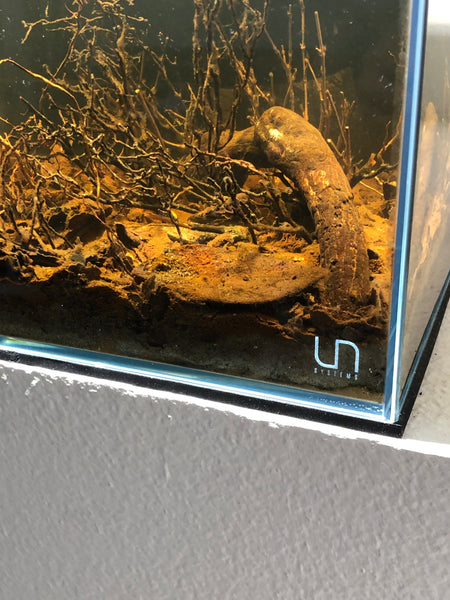

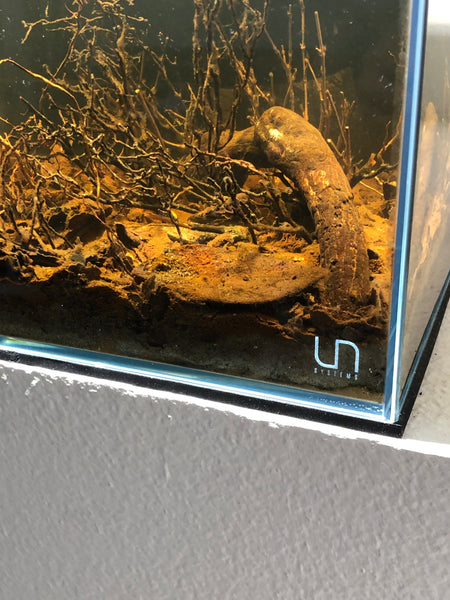

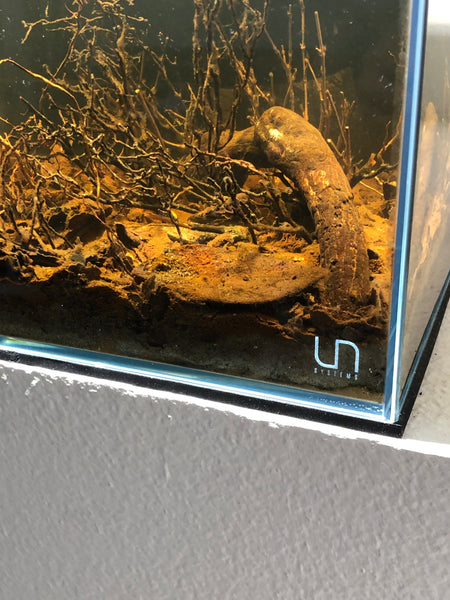

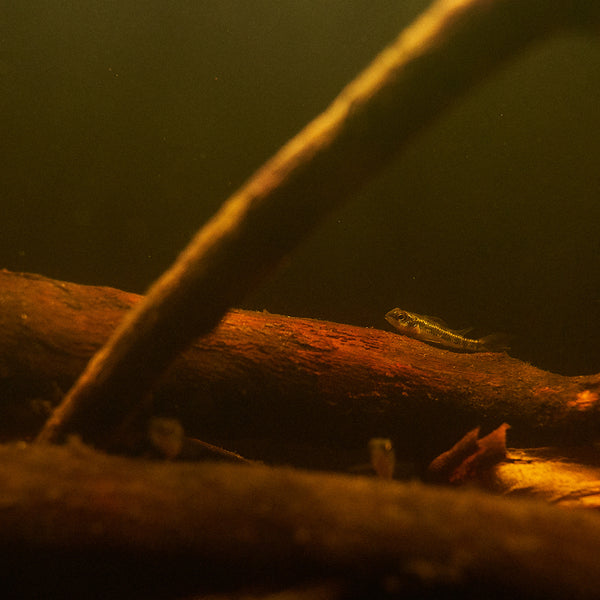

It's not "dirty"- it's perfect.

We receive a lot of questions about the maintenance of botanical-method aquariums. And it makes a lot of sense, because the very nature of these aquariums is that they are stocked, chock-full of seed pods and leaves, all of which contribute to the bio load of the aquarium- all of which are in the process of breaking down and decomposing to some degree at any given moment.

It's not so much if you have to pay attention to maintenance with these tanks- it's more of a function of how you maintain them, and how often. Well, here's the "big reveal" on this:

Keep the environment stable.

Environmental stability is one of the most important- if not THE most important- things we can provide for our fishes! To me, it's more about doing something consistently than it is about some unusual practice done once in a while.

Like, ya' know- water exchanges.

Obviously, water exchanges are an important part of any aquarium husbandry regimen, and I favor a 10% weekly exchange. Iit's the regimen I've stuck with for decades, and it's never done me wrong. I think that with a botanical influenced aquarium, you've got a lot of biological material in there in addition to the fishes (you know, like decomposing leaves and softening seed puds- stuff like that), and even in well-managed, biologically-balanced aquarium, you still want to minimize the effects of any organics accumulating in a detrimental manner.

This piece is not really about water changes, and frankly, you can utilize whatever schedule/precentage works for you. The 10% weekly has worked for me; you may have some other schedule/percentage. My advice: Just do what works and adjust as needed.

Enough said.

Of course, the other question I receive all the time about botanical method aquairums is, "Do you let the leaves decompose completely in your tank, or do you remove them?"

I have always allowed leaves and botanicals to remain in my system until they completely decompose.

This is generally not a water-quality-affecting issue, in my experience, and the decision to remove them is more a matter of aesthetic preferences than function. There are likely times when you'll enjoy seeing the leaves decompose down to nothing, and there are other times when you might like a "fresher" look and replace them with new ones relatively soon.

It's your call.

However, I believe that the benefits of allowing leaves and botanicals to remain in your aquariums until they fully decompose outweigh any aesthetic reservations you might have. A truly natural functioning-and looking- botanical method aquarium has leaves decomposing at all times. There are, in my opinion, no downsides to keeping your botanical materials "in play" indefinitely.

I have never had any negative side effects that we could attribute to leaving botanicals to completely break down in an otherwise healthy, well-managed aquarium.

And from a water chemistry perspective?

Many, many hobbyists (present company included) see no detectable increases in nitrate or phosphate as a result of this practice.

Of course, this has prompted me to postulate that perhaps they form a sort of natural "biological filtration media" and actually foster some dentritifcation, etc. I have no scientific evidence to back up this theory, of course (like most of my theories, lol), other than my results, but I think there might be a grain of truth here!

Remember: A truly "Natural" aquarium is not sterile. It encourages the accumulation of organic materials and other nutrients- not in excess, of course.

The love of pristine, sterile-looking tanks is one of the biggest obstacles we need to overcome to really advance in the aquarium hobby, IMHO. Stare at a healthy, natural aquatic habitat for a bit and tell me that it's always "pristine-looking..."

Lose the "clean is the ultimate aesthetic" mindset. Please.

"Aesthetics first" has created this weird dichotomy in the hobby.

Like, people on social media will ooh and awe when pics of beautiful wild aquatic habitats- many of which absolutely looked nothing like what we do in aquariums- are shared. They'll comment on how amazing Nature is, and admire the leaf litter and tinted water and stuff.

Yet, when it comes time to create an aquarium, they'll almost always "opt out" of attempting to create such a tank in their own home, and instead create a surgically-sterile aquatic art piece instead.

Like, WTF?

Why is this?

I think it's because we've been convinced by...well, almost everybody in the hobby- that it's not advisable or practical- or even possible- to create a truly functional natural aquarium system. It's easier to look for the sexiest named rock and designer wood and mimic some "award winning" 'scape instead.

Ouch.

I think that many hobbyists have lost sight of the fact that there are enormous populations of organisms which reside in their aquariums which process, utilize, and assimilate the waste materials that everyone is so concerned about. We eschew natural methods in place of technology, because it's in our minds that "natural methods" = "aesthetically challenged."

So we go for expensive filters...We've become convinced that technology is our salvation.

The reality is that a convergence of simple technology and embracing of fundamental ecology is what make successful aquariums- well-successful. In many cases (notice the caveat "many"...) you don't need a huge-capacity, ultra-powerful high-priced filter to keep your tank healthy. You don't need massive water exchanges and ultra meticulous water exchange/siphoning sessions to sustain your aquarium for indefinite periods of time.

What you need is a combination of a decent filter system, a regular schedule of small simple water exchanges, and a healthy and unmolested microbiome of beneficial organisms within your aquarium.

Let Nature do Her thing.

Biofilms, fungi, algae...detritus...all have their place in the aquarium. Not as an excuse for lousy or lazy husbandry- but as supplemental food sources which also happen to "power" the ecology in our tanks.

Let's just focus on our BFFs, the fungi, for a few more minutes. We've given them love for years here...long before hashtags like "#fungal Friday "or whatever became a "thing" on The 'Gram.

And of course, as we've discussed many times here, fungi are actually an important food item for other life forms in the aquatic environments tha we love so much! In one study I stumbled across, gut content of over 100 different aquatic insects collected from submerged wood and leaves showed that fungi comprised part of the diet of more than 60% of them, and, in turn, aquatic fungi were found in gut content analysis of many species of fishes!

One consideration: Bacteria and fungi that decompose decaying plant material in turn consume dissolved oxygen for respiration during the process.

This is one reason why we have warned you for years that adding a huge amount of botanical material at one time to an established, stable aquarium is a recipe for disaster. There is simply not enough fungal growth or bacteria to handle it. They reproduce extremely rapidly, consuming significant oxygen in the process.

Bad news for the impatient.

So just be patient. Learn. Embrace this stuff.

Support. Co-dependency. Symbiosis. Whatever you want to call it- the presence of fungi in aquatic ecosystems is extremely important to other organisms.

You can call it free biological filtration for your aquarium!

In the botanical-method aquarium, ecology is 9/10's of the game. Think about this simple fact:

The botanical materials present in our systems provide enormous surface area upon which beneficial bacterial biofilms and fungal growths can colonize. These life forms utilize the organic compounds present in the water as a nutritional source.

GREAT news for the patient, the studious, and the accepting.

Think about this: These life forms arrive on the scene in Nature, and in our tanks, to colonize appropriate materials, to process organics in situ on the things that they're residing upon (leaves, twigs, branches, seed pods, wood, etc.).

So removing it is, at best, counterproductive.

Yeah, if you intervene by removing stuff, bad things can happen. Like, worse things than just a bunch of gooey-looking fungal and biofilm threads on your wood. Your aquarium suddenly loses its capability of processing the leaves and associated organics, and- who's there to take over?

Okay, I'm repeating myself here- but there is so much unfounded fear and loathing over aquatic fungi that someone has to defend their merits, right? Might as well be me!

My advice; my plea to you regarding fungal growth in your aquarium? Just leave it alone. It will eventually peak, and ultimately diminish over time as the materials/nutrients which it uses for growth become used up. It's not an endless "outbreak" of unsightly (to some) fungal growth all over your botanicals and leaves.

It goes away significantly over time, but it's always gonna be there in a botanical method aquarium.

"Over time", by the way is "Fellman Speak" for "Please be more fucking patient!"

Seriously, though, hobbyists tend to overly freak out about this kind of stuff. Of course, as new materials are added, they will be colonized by fungi, as Nature deems appropriate, to "work" them. It keeps going on and on...

It's one of those realities of the botanical-method aquarium that we humans need to wrap our heads around. We need to understand, lose our fears, and think about the many positives these organisms provide for our tanks. These small, seemingly "annoying" life forms are actually the most beautiful, elegant, beneficial friends that we can have in the aquarium. When they arrive on the scene in our tanks, we should celebrate their appearance.

Why?

Because their appearance is yet another example of the wonders of Nature playing out in our aquariums, without us having to do anything of consequence to facilitate their presence, other than setting up a tank embracing the botanical method in the first place. We get to watch the processes of colonization and decomposition occur in the comfort of our own home. The SAME stuff you'll see in any wild aquatic habitat worldwide.

Amazing.

And the end result of the work of fungal growths, bacteria, and grazing organisms?

Detritus.

"Detritus is dead particulate organic matter. It typically includes the bodies or fragments of dead organisms, as well as fecal material. Detritus is typically colonized by communities of microorganisms which act to decompose or remineralize the material." (Source: The Aquarium Wiki)

Well, shit- that sounds bad!

It's one of our most commonly used aquarium terms...and one which, well, quite frankly, sends shivers down the spine of many aquarium hobbyists. And judging from that definition, it sounds like something you absolutely want to avoid having in your system at all costs. I mean, "dead organisms" and "fecal material" is not everyone's idea of a good time, ya know?

Literally, shit in your tank, accumulating. Like, why would anyone want this to linger- or worse- accumulate- in your aquarium?

Yet, when you really think about it and brush off the initial "shock value", the fact is that detritus is an important part of the aquatic ecosystem, providing "fuel" for microorganisms and fungi at the base of the food chain in aquatic environments. In fact, in natural aquatic ecosystems, the food inputs into the water are channeled by decomposers, like fungi, which act upon leaves and other organic materials in the water to break them down.

And the leaf litter "community" of fishes, insects, fungi, and microorganisms is really important to these systems, as it assimilates terrestrial material into the blackwater aquatic system, and acts to reduce the loss of nutrients to the forest which would inevitably occur if all the material which fell into the streams was simply washed downstream!

That sounds all well and good; even grandiose, but what are the implications of these processes- and the resultant detritus- for the closed aquarium system?

Is there ever a situation, a place, or a circumstance where leaving the detritus "in play" is actually a benefit, as opposed to a problem?

I think so. Like, almost always.

In years past, aquarists who favored "sterile-looking" aquaria would have been horrified to see this stuff accumulating on the bottom, or among the hardscape. Upon discovering it in our tanks, it would have taken nanoseconds to lunge for the siphon hose to get this stuff out ASAP!

In our world, the reality is that we embrace this stuff for what it is: A rich, diverse, and beneficial part of our microcosm. It provides foraging, "Aquatic plant "mulch", supplemental food production, a place for fry to shelter, and is a vital, fascinating part of the natural environment.

It is certainly a new way of thinking when we espouse not only accepting the presence of this stuff in our aquaria, but actually encouraging it and rejoicing in its presence!

Why?

Well, it's not because we are thinking, "Hey, this is an excuse for maintaining a dirty-looking aquarium!"

No.

We rejoice because our little closed microcosms are mimicking exactly what happens in the natural environments that we strive so hard to replicate. Granted, in a closed system, you must pay greater attention to water quality, but accepting decomposing leaves and botanicals as a dynamic part of a living closed system is embracing the very processes that we have tried to nurture for many years.

And it all starts with the 'fuel" for this process- leaves and botanicals. As they break down, they help enrich the aquatic habitat in which they reside. Now, in my opinion, it's important to add new leaves as the old ones decompose, especially if you like a certain "tint" to your water and want to keep it consistent.

However, there's a more important reason to continuously add new botanical materials to the aquarium as older ones break down:

The aquarium-or, more specifically- the botanical materials which comprise the botanical-method aquarium "infrastructure" acts as a biological "filter system."

In other words, the botanical materials present in our systems provide enormous surface area upon which beneficial bacterial biofilms and fungal growths can colonize. These life forms utilize the organic compounds present in the water as a nutritional source.

Think about that concept for a second.

It's changed everything about how I look at aquarium management and the creation of functional closed aquatic ecosystems.

It's really put the word "natural" back into the aquarium keeping parlance for me. The idea of creating a multi-tiered ecosystem, which provides a lot of the requirements needed to operate successfully with just a few basic maintenance practices, the passage of time, a lot of patience, and careful observation.

It takes a significant mental shift to look at some of this stuff as aesthetically desirable; I get it. However, for those of you who make that mental shift- it's a quantum leap forward in your aquarium experience.

It means adopting a different outlook, accepting a different, yet very beautiful aesthetic. It's about listening to Nature instead of the asshole on Instagram with the flashy, gadget-driven tank. It's not always fun at first for some, and it initially seems like you're somehow doing things wrong.

It's about faith. Faith in Mother Nature, who's been doing this stuff for eons. Mental "unlocks" are everywhere...the products of our experience, acquired skills, and grand experiments. Stuff that, although initially seemingly trivial, serves to "move the needle" on aquarium practice and shift minds over time.

A successful botanical method aquarium need not be a complicated, technical endeavor; rather, it should rely on a balanced combination of knowledge, skill, technology, and good judgement. Oh- and a bunch of "mental shifts!"

Take away any one of those pieces, and the whole thing teeters on failure.

Utilize all of these things to your advantage and enjoy your hobby more than ever!

Remember, your botanical method aquarium isn't "dirty."

It's perfect.

Just like Nature intended it to be.

Stay bold. Stay grateful. Stay thoughtful. Stay curious. Stay diligent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

It's cool enough.

I'm trying to break though to some of you who have been really beaten down by the insanity that is social media in the aquarium hobby. A bunch of you have reached out to me lately and were concerned about the reception some of your work is getting from self proclaimed "experts."

Enough is enough.

Most of these "experts" don;'t have enough experience with botanical-method aquariums to levy any sort of criticism at all with any degree of credibility or meaning. Yet, they DO know that these types of aquairums differ substantially from what THEY know to be "the way" to do stuff in the hobby, so it's really easy for them to criticize. After all, what you're doing is not the same as everyone else, so it MUST be wrong, no?

Why do we as a hobby seem to find such comfort in doing what everyone else does?

Why do we have to copy everyone else's tank in order to be considered "serious." And who is it that has the right to judge or make bold proclamations about your work, anyways? Who the hell said that what you do isn't "good enough"; or somehow isn't "cool", or whatever?

In the aquarium world, we spend far, far too much time working about being accepted for our work, or hoping that it stands up to the scrutiny of others. I'm not the first person to tell you this, I know- but you need to just forget that bulkshit right now and do what YOU do best- execute the type of aquarium or aquascape or habitat that makes YOUR heart sing...NOT the one that's gonna garner the most likes on The 'Gram.

"That won't work! Your aquarium will be filled with decomposing leaves and detritus...and...!"

WHO THE FUCK CARES!

I mean, really. Surely, these self-proclaimed critics MUST have something better to do than shit on your work, right? So, really, you should pity them, not even stress out about them or their comments.

One of the criticisms that our hobby speciality has received a lot over the years is that we appear ( to the uninformed or uninitiated) to be embracing neglect of basic husbandry in our tanks. On it's face, this is an absurdity, but it just shows how incredibly superficial many people can be, failing to go beyond a pic of a tank filled with decomposing leaves, etc., and reconciling it with what they've been indoctrinated in the hobby to believe is a "proper" or "well maintained" tank.

I've heard lots of criticisms over the years from hobbyists who assert that our tanks are filled with "nuisances", like biofilms, fungal growths, etc., and that our acceptance of them is based on laziness and a disregard for the "rules" of aquarium keeping.

Wrong on so many fronts...

First off, it kind of begs the question...what's a "nuisance", anyways? I mean, sure, to a lot of hobbyists, algae growth or fungal growth is unsightly, and detracts from their desired aesthetics. However, in and of itself, it's not really harmful, right? Now, sure, you could make the argument that it can "smother" plants, which is most definitely problematic. However, when it grows over substrate or "undefended" surfaces, like the glass or filter intakes, etc., is it a "problem", other than simply aesthetically incompatible with your vision for how you want your tank to look?

Algae, as we all know, is actually a valuable and integral part of the aquatic ecosystem, and is essential for aquatic life as we know it. In fact, I remember reading lots of articles about marine aquariums from the late 1970's and early eighties which actually celebrated the idea of a "luxurious" growth of green algae over your dried coral skeletons, etc.!

It was seen as a key indicator that your aquarium was well-suited for higher life forms (ie; fishes!). In addition to "cycling" your tank, you wanted to see that algae growth! Hobbyists literally added cultures of live marine algae to their tanks during the initial start up phase to "seed" them.

My, how times have changed!

Despite the indisputable scientific fact that algae is an essential component of the aquatic ecosystem, and the hobby's semi-embrace of "natural", hobbyists still freak the fuck out when algae show up in their tanks. Show me a so-called "Nature Aquarium" where there is even a visible speck of the stuff! Hobbyists scrub and siphon and pick at every centimeter of visible algae growth in these tanks, and consider it a shameful thing to have any of it in their tanks!

And in our world of function-forward nature-embracing botanical method aquairums, we celebrate the appearance of biofilms. fungal growths, decomposing leaves, and botanical detritus much the way the Marine aquarists of the 1970's and early eighties celebrated the appearance of green algae in their tanks!

These life forms are viewed as foundational components of the closed aquatic ecosystems which we are attempting to assemble in our tanks. We embrace them not as a submission to lax maintenance habits or blissful ignorance, but rather, as an indication that life is functioning as it should in our tanks.

As a hobby, I think we unnecessarily make lot of stuff "problems."

When you think about it, many concepts in aquarium keeping started out as "problems", or were considered “impossible” until someone made them work.

Now, sure, I get the fact that Nature imposes "rules" on what we can do. There are consequences- often dire- to trying to break or circumvent natural processes. For example, trying to avoid the nitrogen cycle, or attempting to keep incompatible fishes together. Much of this stuff is common sense. However, it doesn't keep a lot of people from trying to "beat the system."

Now look- I'm all for trying new ideas-pushing the limits of what's possible, and questioning the "status quo" in the hobby. However, trying to "game"eons of natural processes in order to create some sort of a "hack" doesn't only not work- it's stupid.

THAT is a problem that we create.

You can, however, push the limits and break new ground by working within the boundaries of natural processes. That's advancement. That's progress. Innovation.

Many of us are working every day to progress in the hobby.

It took doing things that we hadn't previously done before- researching exactly what it was, what is required to make "blackwater"- and doing some things which were perceived by the majority of hobbyists as unconventional to get there.

But we did.

And now, we approach keeping botanical method aquariums not as a "problem" to overcome, but an approach which requires us to do specific things in order to do so successfully.

Look, it wasn't like we were creating warp drive or nuclear fusion. But it is an example- one of many in our hobby, of an evolution which simply required us to look at what exactly we wanted to accomplish, understand what it was, and to develop ways to work within the requirements and parameters laid out by Nature to do it in our aquariums. It's still very much a "work in progress", but we're well on the way to making botanical method aquariums far more common in the hobby.

And definitely not a "problem."

Funny thing is that, in reality, it IS a sort of an evolution, isn't it? A little advancement from where we are in the hobby before.

I mean, sure, on the surface, this doesn't seem like much: "Toss botanical materials in aquariums. See what happens." It's not like no one ever did this before. And to make it seem more complicated than it is- to develop or quantify "technique" for it (a true act of human nature, I suppose) is probably a bit humorous.

Yeah, I guess I can see that...

On the other hand, the idea behind this practice is not just to create a cool-looking tank...And, we DO have some "technique" behind this stuff...

And it's not about making excuses for abandoning aquarium "best practices" as some justification for allowing our tanks to look like they do.

We don't embrace the aesthetic of dark water, a bottom covered in decomposing leaves, and the appearance of biofilms and algae on driftwood because it allows us to be more "relaxed" in the care of our tanks, or because we think we're so much smarter than the underwater-diorama-loving, hype-mongering competition aquascaping crowd.

Well, maybe we are? 😆 (I promise to keep dissing these people until they put their vast skills to better use in the hobby...Sorry, lovers of underwater beach seems and "Hobbit forests.." You can do a lot better.)

I mean, we're doing this stuff for a reason: To create more authentic-looking, natural-functioning aquatic displays for our fishes. To understand and acknowledge that our fishes- and their very existence- is influenced by the habitats in which they have evolved.

We've mentioned ad nauseum here that wild aquatic habitats are influenced greatly by the surrounding geography and flora of their region, which in turn, have considerable influence upon the population of fishes which inhabit them, as well as their life cycle.

The simple fact of the matter is, when we add botanical materials to an aquarium and accept what occurs as a "result"-regardless of wether our intent is just to create a different aesthetic, or perhaps something more- we are to a very real extent replicating the processes and influences that occur in wild aquatic habitats in Nature.

The presence of botanical materials such as leaves in these aquatic habitats is foundational to their existence, as it is in our aquarium approach.

And the fact that they recruit biofilms and fungal growths, and break down over time in our tanks is simply part of the natural process. We can consider this a "problem" which needs to be 'mitigated" somehow, or we can make the effort to understand how these processes and occurrences can benefit the little microcosms which we have created in our aquariums.

Anyone who's kept tropical fishes for any appreciable length of time does stuff that, while maybe not intentional, doesn't exactly fit the commonly accepted "best practices" of aquarium keeping. Stuff that perhaps doesn't provide the fishes under your care with stable, comfortable environmental conditions.

Maybe you slacked off on water exchanges for a protracted period of time. Perhaps you forgot to replace your filter media...Maybe you added a few too many fishes to that 20 gallon aquarium...What about the time you went on vacation and forgot to set up a means to feed them while you were away for 10 days? Or the time the heater failed and the water temp never got above 67 degrees F (19 C ) for like a week before you realized it?

These "lapses" are not exactly something that you want to have happen.

And yet, somehow- the fishes survived, right?

Yeah. They did.

Why?

Well, perhaps they're a lot more adaptable than we give them credit for, right?

Sure, fishes will likely always do best when provided with consistent, stable environmental conditions; conditions consistent with the environmental parameters under which they've evolved for eons.

Another example? I was talking with a friend a few days back about how disruptive, yet necessary "deep cleanings" that we give our tanks now and again . I was arguing that, in reality, they're not so disruptive, and likely mimic things that happen in Nature.

My hypothesis was that these were sort of analogous to seasonal and/or weather-related events, such as monsoonal rains, influxes of water into streams, etc. etc., and that they are probably more "traumatic" to the aquarist than they are to the fishes, which have evolved to handle them over eons.

What sparked this was a little epiphany I had a number of years ago, caused by just such a "disruptive" event. I was looking at my office tank one day, as it was "recovering", if you will, from the thorough cleaning it received days before, and sort of marveled at the progression of things that happened. I kind of think I was spot-on in my thinking here for a change.

After the first 24 hours, I was a little down on myself, because I stirred up surprisingly large amount of detritus, which sort of started to settle on the wood, leaves, etc. The water was a little bit turbid. The formerly crystal-clear, sparkling clean (yet very brown) tank had a bit of "dirtiness" to it. It wasn't a huge amount, mind you- but sufficient enough for me to take notice and think to myself, "Damn, that looks kind of...different!"

"Different" = "shitty" to a fish geek....

Notice I didn't' freak out and think, "Oh my God! This tank is a mess...I need to do another massive water change...Need to..." Yeah. I stayed calm...I sort of believe in that theory we talked about. The theory that, in most cases, a healthy closed ecosystem like an aquarium will rebound from a seemingly significant event like the "Great Detritus Storm of 2016", and return to its glory really quickly with minimal intervention on the part of the aquarist. The theory that, in nature, disruptive events like storms and rains typically have more value than problems associated with them for the fishes.

Well, fast forward another couple of days, and I thought that my time-honed hypothesis was proven right. All of that detritus more or less cleared up..Settled...or captured by the filter? Probably to some extent...But the most remarkable "cleansing" of the detritus influx was conducted by the fishes themselves. I mean, especially my characins -which really went to town on this stuff, spending pretty much all day picking at the wood, substrate, leaves, botanicals.

Were they consuming the detritus itself?

Um, probably not as much as I'd like to think; however, some of the materials bound up in the detritus were probably quite good to them. And this is borne out by my research into the natural stomach contents of many fishes. Detritus, organic materials, and insects, fungal growths and other materials bound up in a matrix of this stuff is a huge component of the diet of many fishes in Nature.

And of course, in some instances, the botanical materials themselves are feed...as are the biofilms, fungi, sugars and matrix of materials bound up in detritus and small particles of "stuff" in our leaf litter and such.

I remember marveling at how the fish were so "busy" at this foraging on the newly-uncovered "bounty", that I refrained from supplemental feeding for the nextt several days, and they were thicker and fatter than before the "event" occurred!

And the tank? It was sparkling...crystal clear, with the beautiful brown tint we love so much around here, in full glory. In retrospect, I'm thrilled that I held off from the "primal aquarist urge" to panic, reach for the siphon, and do another disruptive maintenance. This was a mindset-shaping even for me! I would have completely missed the interesting behavior of my fishes, and the gorgeous "rebound" of the aquarium during what would have been my frantic intervention. Rather, I made the rather "mature" decision to just pick up where I left off and conduct my regular weekly water exchange later that week..

So the simple takeaway from this little epiphany was: Not everything that seems like a "problem" is indeed a "problem." Not everything requires our rapid intervention. Or any intervention, for that matter. Nature's got this act honed to a fine sheen...We can coax it along, or even jump right in the mix...however, the reality is that these processes are certainties if left to themselves. There are reasons why stuff like this happens in nature, and reasons why our animals have adaptive mechanisms to deal with them. We just have to be patient, observant, and engaged.

All qualities which virtually every successful aquarist has anyways, right?

Yeah.

I'm obsessed with this, as are many of you- and it's part of what interested me in the idea of using botanical materials in aquariums in the first place- an attempt to replicate some of the physical, environmental, and chemical characteristics of the environments from which they come from in the wild.

However, it's no secret that fishes will adapt to more easily-provided "captive conditions", even reproducing under them. You only need to think about all of the captive-bred tetras which, despite evolving in soft, acidic conditions, often thrive and breed in hard, alkaline water.

There's not really a mysterious reason why this is.

The reality is that most fishes can adjust and adapt to changing or challenging conditions if you give them a little help….The "help" is providing aquarium conditions which are chemically stable, and in the case of those measures which reflect the levels of metabolic waste in the water (nitrite, ammonia, nitrite and phosphate)- low and stable. Keep 'em well fed and stable.

It really boils down to common sense husbandry.

Stability- or, more specifically, stability within a given range of measure- is what always seems to keep fishes alive and thriving. Continuously, quickly changing, and wildly varying environmental parameters are simply stressful for fishes, and, while often not killing them quickly outright, will result in continuous stress, which can lead to disease and other medical problems over time.

That being said, it's not imperative that every single parameter in your aquarium needs to be perfectly stable and "spot on" to hobby-grade "standards". And out concern over any variation from perfection is really unfounded, IMHO.

We get too stressed-out over minutiae, IMHO.

To get a perspective, just have a chat with some non-fish-keeping acquaintances about stuff that happens in your aquariums.

Don't you think that sometimes, as hobbyists, we tend to get a bit- well, "overly concerned" about stuff that non-hobbyists don't understand? Or, perhaps they do-more than we can even comprehend- and will occasionally come up with some "pearls of wisdom" about fishkeeping that blow us away!

Case in point:

Not too many years ago, I recall walking into my office early one morning, and I immediately was taken aback. Apparently, one of my light timers had failed, and the one of my tank lights remained on all night.

No biggie, right? Well except for the fact that it was my South American-igarape-inspired leaf litter tank, and I recently added some cool wild characins to the tank, acclimated and carefully quarantined...and then- THIS had to happen, and....you know where I'm going with this?

This was going through my mind:

"Omigod, the fishes didn't get any dark period...they've been seriously stressed..."

You will say that this wouldn't bother you- but you're totally lying! It would bother the shit out of you, too! I know that it would, 'cause you're a fish geek. It's part of what we all do.

Of course, I relayed this concern to my wife later in the day, when we touched base and asked each other how are days were progressing.

To which my wife, not at all a fish geek, yet ever the pragmatist, noted, "You know, Scott, sometimes, unexpected things happen in the Amazon."

Woah.

She was on to something there.

And it's not just lilt old me who freaks out about stuff like this. I know for a fact...

It's a fish-geek thing.

I think, that as hobbyists, we tend to get caught up in every little minute detail of the little worlds we've created for our fishes- so much so that we often forget the one underlying truth about them:

They're living creatures, which have evolved over eons to adapt to and deal with changes in their environment-big and small...or even insignificant, like an excessive amount of light one evening.

I mean, there must have been some natural precedent for this, right? Some atmospheric phenomenon- or combination of phenomenon-which rendered the night sky inordinately bright one evening at some point in the long history of the world?

Yeah. Exactly.

Think about it for a second.

I think this high level of concern-this "overkill", if you will, on the part of all hobbyists is based on the fact that we take great pains to assure that we've created perfect little captive environments for our fishes, and do everything we can to keep them stable and consistent.

When something out of the ordinary happens- a pump fails, a heater sticks in the "on" position, we forget to feed, etc.- we tend to get a little bit, oh...crazy, maybe?

Look, I get it: When a critical piece of environmental control equipment fails (like a heater), especially during a cold spell or heatwave, it could be life or death for your fishes. If you're about to spawn a particularly picky fish or rear some fry, it could be a serious problem. You can't really downplay those concerns. However, some of the less dramatic, non-life-threatening issues, such as a light staying on or off longer than usual one evening, a circulation pump stopping unexpectedly for a couple of hours, or forgetting to change the carbon in the filter one week, don't really create that much of a problem for your fishes when you really think about it objectively, do they?

Nah.

At some time during the exisience of our fishes in the wild, there was a temporary blockage in the Igarape in which they resided, slowing down the normal flow. At some point, there might have been a once-in-a-century cold morning in the tropics, right? At some point, the swarm of Daphnia or Cadis Fly larvae that were so abundant for months at a time, weren't...

In most instances, the animals that we keep are not so delicate, and the closed environments we provide aren't running so "close to the edge" that we should panic when some random factor changes things up one day. And consider this: When we purchase our fishes, they are unceremoniously netted out of the tank (or stream, lake, river, etc.) environment in which they reside, placed in a plastic bag, transported for who knows how long, and possibly making a few stops on the way before ultimately landing in our aquarium.

That's a LOT of changes to cope with. Stress.

But guess what? Fishes manage to deal with it. Somehow.

Sure, our first choice is to have rock-solid parameters and environmental conditions for our fishes 24/7/365, but sometimes stuff happens that throws a proverbial "wrench" into our plans. We have to be adaptable, flexible...just like our fishes apparently are.

So next time your light doesn't come on, or you forget to feed your fishes as you rush off to work some morning, don't stress out over it. They'll be fine. Keep calm. Always keep your concern high, but don't let obsessing over your fishes keep you from focusing on the even more important things in life (yeah, there are a few, right?).

And remember, sometimes unexpected things DO happen in the Amazon.

There is one fundamental truth, really:

The aquarium hobby isn’t difficult.

However, it CAN be when we make it that way by imposing our own barriers and obstacles to success. And that includes stressing out over what, in reality, are really not devastating issues for our fishes. Of course, you also have to realize that common sense is so important.

One of the unusual inconsistencies that I’ve noticed is that, sometimes, you’ll see information about a specific fish on a website, describing in detail it’s natural habitat.

And many natural aquatic habitats are influenced by their terrestrial surroundings.

There are all sorts of interesting influences on these natural habitats created by the surrounding terrestrial environment and the microbial associations which occur in the substrates, leaves, wood, and other materials which comprise them.

The relationship between terrestrial habitats and the aquatic environment is becoming increasingly apparent- particularly in areas in which blackwater is found. And, the lack of suspended sediments, which create a "nutrient poor" condition in these habitats, doesn't do much to facilitate "in situ" production of aquatic food sources; rather, it places the emphasis on external factors.

Many blackwater systems are simply too poor in nutrients to offer alternative food sources to fishes.The importance of the relationship between the fishes and their surrounding terrestrial habitat (i.e.; the forests which are inundated seasonally) is therefore obvious. That likely explains the significant amount of insects and other terrestrial food sources that ichthyologists find during gut content analysis of many fishes found in these habitats.

And, as we've hinted on previously- the availability of food at different times of the year in these waters also contribute to the composition of the fish community, which varies from season to season based on the relative abundance of these resources.

Another example of these unique interdependencies between land and water are when trees fall.

It’s not uncommon for a tree to fall in the rain forest, with punishing rain and saturated ground conspiring to easily knock over anything that's not firmly rooted. When these trees fall over, they often fall into small streams, or in the case of the varzea or igapo environments in The Amazon that I'm totally obsessed with, they fall and are submerged in the inundated forest floor when the waters return.

And of course, they immediately impact their (now) aquatic environment, fulfilling several functions: Providing a physical barrier or separation from currents, offering territories for fishes to spawn in, providing a substrate for algae and biofilms to multiply on, and providing places for fishes forage among, and hide in. An entire community of aquatic life forms uses the fallen tree for many purposes. And the tree trunks and parts will last for many years, fulfilling this important role in the aquatic ecosystems they now reside in each time the waters return.

In nature, as we've discussed many times-leaf litter zones comprise one of the richest and most diverse biotopes in the tropical aquatic ecosystem, yet until recently, they have seldom been replicated in the aquarium. I think this has been due, in large part- to the lack of continuous availability of products for the hobbyist to work with, and a lack of real understanding about what this biotope is all about- not to mention, the understanding of the practicality of creating one in the aquarium.

Long-held fears and concerns, such as overwhelming our systems with biological materials, and the overall "look" of decomposing leaves and botanicals in our tanks, have understandably led to this idea being relegated to "sideshow status" for many years. It's only been recently that we've started looking at them more objectively as ecological niches worth replicating in aquariums.

The aquairum world involves a lot of compromises.

It involves a tremendous number of concessions and decisions. And it often comes down to what WE want as hobbyists, versus what the animals under our care NEED.

Sometimes, this can be challenging, putting us at odds with what we know and desire and like. Often, the compromises we make involve doing things for the greater good- sacrificing our preferences for what's best for the life forms we keep.

This is not a bad thing, right?

It's important to understand that we require compromise in order to progress in the hobby. It's also important that we understand what is "normal" for the types of aquariums that we're working with- and why.

We're well on our way to changing the hobby in a positive way. As a community, we're pushing forward in many new directions, challenging established ideas, and breaking new ground.

Stay on it. Stay inspired. Stay bold. Stay diligent. Stay creative...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

Fast forward to the beginning...

Nature has been working with terrestrial materials in aquatic habitats for uncounted eons.

And Nature works with just about everything you throw at her.

She'll take that seemingly "unsexy" piece of wood or rock or bunch of dried leaves, and, given the passage of time, the action of gravity and water movement, and the work of bacteria, fungi, and algae- She'll mold, shape, evolve them into unique and compelling pieces, as amazing as anything we could ever hope to do...

If we give her the chance.

If we allow ourselves to look at her work in context.

If we don't worry when things go "sideways."

If we don't give up.

Always have faith in Nature.

She'll challenge you. She'll tempt you. She'll school you. But She'll also educate you, indoctrinate you into her ways, and take you under her wing...if you let Her.

Let Nature handle some of the details... She pretty much never messes them up! Don't fight Her. Understand her. Don't be afraid to cede some of the work to Her.

Botanical-method aquariums are not not "just a look." Not just an aesthetic. Not just a "trend." Not even just a mindset...

Rather, they're a way to incorporate natural materials to achieve new and progressive results with the fishes and plants we've come to love so much. And they incorporate many of the same "best practices" that we've come to know and love over the past century of modern aquarium keeping. Our success or failure is completely dependent upon how we apply many of these time tested approaches.

If there is a commonality among successful hobbyists in any aquarium speciality, it's that they follow fundamentals- common core principles of aquairum keeping. It's not additives, or fancy gear- it's patience and consistency. Routine and following a philosophy of aquarium husbandry.

First and foremost is patience.

I feel that we don't celebrate patience quite enough.

Are you one of those people who loves to have stuff right now? The kind of person who just wants your aquarium "finished"- or do you relish the journey of establishing and evolving your little microcosm?

I'm just gonna go out on a limb here and postulate that you're part of the latter group.

Have you ever completed an aquascape and stepped back and looked at it in its most "embryonic" phases, and thought to yourself, "This looks good?" The pristine glass, perfect deal wood, sparkling gravel...The scent of a brand new aquarium...

Well, of course you have! It's part of the game.

It's a total sensory experience, isn't it?

To me, however, the real "magic" in an aquarium happens not when it's new and pristine, but after a few weeks or months, when it develops that "patina" of micro algae, fungal growths, and a bit of detritus...the "matte" sheen of biofilm on the substrate...And when your tank develops that earthy, clean, alive smell.

That, to me, is when an aquarium really feels "alive" and evolving.

When it comes to maintenance of aquariums, I'm a big believer in removing algae from the front glass and "excessive" films from the driftwood or other materials...But I don't go crazy about it like I used to. Like many of you, I let some of those natural processes evolve, just like the tank itself...

I think I tend to spend less time and energy removing "offensive" algae growth manually, and spend far more time and energy controlling and eliminating the root causes of its appearance: Excess nutrients, too much light, lax maintenance practices, etc. It's not that I don't think I should be scraping algae- it's just that it seems to make more sense to "nip it in the bud" and attack the underlying causes of it's growth.

Understanding the dynamic in a closed aquarium system is really important.

There is another aspect to appreciating it: Letting a system "evolve" and find its way, with a little bit of guidance (or botanicals, as the case may be) from time to time, is beautiful to me...Watching the "bigger picture" and realizing that all of these "components" are part of a bigger "whole."

When I first approached botanical method tanks a couple of decades ago, this was a definite of mental shift for me, right along with accepting the biofilms, blackwater, and decomposing leaves. Like most of you, I've spent much of my fishy "career" doing "reaction" style aquarium maintenance, breaking out the algae scraper at the first sign of the "dreaded" stuff.

And I've come to realize that taking a more proactive, understanding, and yeah- relaxed approach to so-called "nuisance algae management" has created a much more enjoyable hobby experience for me. And being a bit more accepting about seeing "some" algae growth and such has created far more aesthetically pleasing, naturally-appearing aquariums.

There is nothing wrong with creating a more "clinically sterile-looking" aquarium. Perfectly manicured, impeccably groomed task are beautiful. It's just that there is something about the way nature tends to do things that seems a bit more satisfying to me.

And apparently, for many of you, too!

The beauty is that, like so many things in this hobby- there is no "right" or "wrong" way to approach something as mundane as algae growth and tank "grooming." It's about what works for YOU..what makes you feel comfortable, and what keeps your aquarium healthy.

Regardless of what approach we take, natural processes that have evolved over the eons will continue to occur in your aquarium. You can fight them, attempt to stave them off with elaborate "countermeasures" and labor...or you can embrace them and learn how to moderate and live with them via understanding the processes.

And the algae?

It'll always be there. It's just a matter of how "prominent" we allow it to be.

Simple. And, actually- sort of under our control, isn't it?

And when new think of expanded time frames under which our tanks evolve and operate, what's the big rush to "eradicate" things?

I'm not sure exactly what it is, but when it comes to the aquarium hobby...I find myself playing what is called in many endeavors (like business, sports, etc.) a "long game."

I'm not looking for instant gratification.

I know-we all know- that good stuff often takes time to happen. I'm certainly not afraid to wait for results. Well, I'm not just sitting around in the "lotus position", either- waiting, anyways. However, I'm not expecting immediate results from stuff. Rather, I am okay with doing the necessary groundwork, nurturing the project along, and seeing the results happen over time.

Yeah, that's a "long game."

If you're into tropical fish keeping, it's almost a necessity to have this sort of patience, isn't it? I mean, sure, some of us are anxious to get that aquascape done, get the fishes in there, fire up the plumbing in the fish room, etc. However, we all seem to understand that to get good results- truly satisfying, legitimate results- things just take time. Yeah, I'd love it if some "annual" killifish eggs hatched in one month instead of 7-9 months, for example, but...

I wouldn't complain, but I do understand that there is the world the way it is; and the world the way we'd like it to be.

I'll just say it: Your aquarium likely won't look anything like what you've envisioned for at least 3 months.

And there's absolutely nothing wrong with that.

What's the rush? From day one, your botanical method aquarium will simply look different than any other tank that you've ever kept. It will by virtue of the fact that it's set up differently than any other tank you've ever kept!

So, why not simply enjoy THAT?

I also think that we as a hobby tend to glorify the "finished product", with very little discussed- or shared on social media- about the journey itself. I believe that, if presented with the same gusto as finished tanks by hobbyists active on social media, stories about the journey of a botanical method aquarium can be incredibly compelling- even as compelling as the "finished" product.

I think that, by sharing such journeys, we can create an atmosphere of excitement around process- a huge thing for our hobby.

What it takes to get there is consistency and patience...

I have to implore you to deploy absurd amounts of patience and to employ "radical cal consistency" in your maintenance efforts. "Radical" in the sense that you simply have to become fanatical. Consistency meaning you do it regularly. Not sometimes, or when it feels right- but regularlary. Always.

Consistent habits create consistent environmental parameters, without a doubt.

As you've heard me mention ad nauseum here, natural rivers, lakes, and streams, although subject to seasonal variations and such, are typically remarkably stable physical environments, and fishes and plants, although capable of adapting to surprisingly rapid environmental changes, have really evolved over eons to grow in consistent, stable conditions.

Consistency.

In the botanical-influenced, low alkalinity/low pH blackwater environment, consistency is really important. Although these tanks are surprisingly easy to manage and run over the long haul, consistency is a huge part of what keeps these speciality systems running healthily and happily for extended periods of time. It wouldn't take too much beginning neglect or even a little sloppiness in husbandry to start a march towards increasing nitrate, phosphate, and their associated problems, like nuisance algae growth, etc.

Consistency. Regular maintenance. Scheduled water changes. The usual stuff. Nothing magic here. Nothing that a sexy $24.00 bottle of bacterial culture is going to replace.

Nothing that you, as an experienced hobby don't already know. Right?

Just looking at your tank and its inhabitants will be enough to tell you if something is amiss. More than one advanced aquarist has only half-jokingly told me that he or she can tell if something is amiss with his/her tank simply by the "smelI!" get it- excesses of biological activities do often create conditions that are detectible by scent!

It's as much about consistency-consistency in practices and procedures- as it is about hitting those "target numbers" of pH, nitrate, etc. If you ask a lot of successful aquarists how they accomplish this-or-that, they'll usually point towards a few things, like regular water changes, good food, and adhering to the same practices over and over again.

Consistency = Stability.

Sure, there might be times you deliberately manipulate the environment fairly rapidly, like a temperature change to stimulate spawning, etc., but for the most part, the successful aquarist plays a consistent game. Most fishes come from environments that vary only slightly during he course of a day, and many only seasonally, so stability is at the heart of "best practice" for aquarists.

So, without further beating the shit out of this, I think we can successfully make the argument that consistency in all manner of aquarium-keeping endeavors can only help your animals. Keeping a stable environment is not only humane- it's playing into the very strength of our animals, by minimizing the stress of constantly having to adapt to a fluctuating environment. As one of our local reef hobbyists likes to say, "Stability promotes success."

Who could argue with that?

I'm sure that you can think of tons of ways that consistency in our fish-keeping habits can help promote more healthy, stable aquariums. Don't obsess over this stuff, but do give some thought to the discussion here; think about consistency, and how it applies to your animals, and what you do each day to keep a consistent environment in your systems.

And don't be fucking lazy.

Don't look for magic potions, shortcuts, or hacks.

Good stuff takes time to achieve.

Stay observant. Stay methodical. Stay diligent. Stay grounded. Stay consistent...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

"Project 18": The turning point.

Okay, that title sounds a lot like some spy thriller or sci-fi action movie. The reality is that it's simply a part of my tank identification "nomenclature." Each year since Tannin began, I committed myself to do at least one major aquairum project, one that really puts down a "marker"- or tests some idea that Ive had in my head. Something that pushes the boundaries of what we do in the botanical-method aquarium.

Despite the "major" descriptor- the tank doesn't have to be a big one. I've had some of my most epic tanks and greatest influential developments arise out of nano tanks. The "Urban Igapo" concept (Project 19), The "Tucano Tangle" (Project 20), the botanical brackish system (Project 17), and our "Java Jungle" (Project 21) all came from tanks of 25 US gallons or less. Each one had outsized impact on my philosophies moving forward.

Each one represented a "turning point" in my personal botanical method aquarium journey.

Of all of the tanks I've played with in the past 5 years, none has had greater impact on me and my future work than the 50-gallon botanical method tank which we called "Project 18". This tank helped move the mark...pushed me into a new era of more thorough, more natural ecosystem creation.

It was the first larger tank in which I really let Nature take control. Let her dictate the pace, the diversity, and the aesthetic.

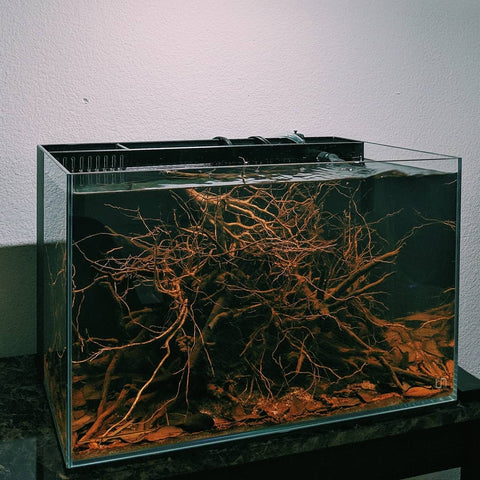

It started quite simply, really.

An almost stupid-looking stack of wood.

Not just any wood, though- Red Mangrove branches. A wood variety that imparts large amounts of tannins into the water. A very "dirty" kind of wood, with lots of textured surface area- perfect for biofilm and fungal colonization.

The idea behind "Project 18" was to accept what Nature does to the materials we use- without any intervention on my part, nor a bent towards placing aesthetics first.

Why?

Well, for one thing, it was to put down my personal "marker" for "Natural" in the aquairum hobby. This word is used too often, and in weird ways, IMHO. Some hobbyists emphasize how "natural" their aquairum is without really looking at the absurdity of how hard they're trying to fight off Nature- by forcing decidedly unnatural combinations of plants and other materials to exist in a highly staged, very precisely manicured world of aesthetic-first philosophy. The result is a beautiful aquairum- one which has natural components, sure- but which could hardly be considered anything but an artistic view of Nature when placed into this context.

I sometimes fear that this burgeoning interest in aquariums intended to replicate some aspects of Nature at a "contest level" will result in a renewed interest in the same sort of "diorama effect" we've seen in planted aquarium contests. In other words, just focusing on the "look" -or "a look" (which is cool, don't get me wrong) yet summarily overlooking the function- the reason why the damn habitat looks the way it does and how fishes have adapted to it...and considering how we can utilize this for their husbandry, spawning, etc.- is only a marginal improvement over where we've been "stuck" with for a while now as the "gold standard" in freshwater aquariums..

Some people are simply too close minded to apply their skills to doing things in a TRULY more natural way.

Some of these people need to just stare at a few underwater scenes for a while and just open their minds up to the possibilities...

We all need to go further.

I'm sure I'm being just a bit over-the-top (oaky, maybe QUITE a bit!), but the so-called "nature aquarium" movement seems to have, IMHO, largely overlooked the real function of Nature, so there is some precedent, unfortunately. A sanitized, highly stylized interpretation of a natural habitat is a start...I'll give 'em that-but it's just that- a start.

The real exciting part- the truly "progressive" part- comes when you let Nature "do her thing" and allow her to transform the aquarium as she's done in the wild for eons.

So, yes- It should go beyond merely creating the "look" of these systems to win a contest, IMHO. Rather, we should also focus on the structural/functional aspects of these environments to create long-term benefits for the fishes we keep in them. We should aim to incorporate things like biofilms, detritus, decomposition into our systems, just as Nature does.

That's a real "biotope aquarium" or 'Nature" aquarium in my book.

That was the philosophy behind "Project 18."

Perhaos the most important things that botanical method aquariums can do is to facilitate the assembly of a "food web" within the system.

To me, these are fascinating, fundamental constructs which can truly have important influence on our aquariums.

So, what exactly is a food web?

A food web is defined by aquatic ecologists as a series of "trophic connections" (ie; feeding and nutritional resources in a given habitat) among various species in an aquatic community.

All food chains and webs have at least two or three of these trophic levels. Generally, there are a maximum of four trophic levels. Many consumers feed at more than one trophic level.

So, a trophic level in our case would go something like this: Leaf litter, bacteria/fungal growth, crustaceans...

In the wild aquatic habitats we love so much, food webs are vital to the organisms which live in them. They are an absolute model for ecological interdependencies and processes which encompass the relationship between the terrestrial and aquatic environments.

In many of the blackwater aquatic habitats that we're so obsessed with around here, like the Rio Negro, for example, studies by ecologists have determined that the main sources of autotrophic sources are the igapo, along with aquatic vegetation and various types of algae. (For reference, autotrophs are defined as organisms that produce complex organic compounds using carbon from simple substances, such as CO2, and using energy from light (photosynthesis) or inorganic chemical reactions.)

Hmm. examples would be phytoplankton!

Now, I was under the impression that phytoplankton was rather scarce in blackwater habitats. However, this indicates to scientists is that phytoplankton in blackwater trophic food webs might be more important than originally thought!

Now, lets get back to algae and macrophytes for a minute. Most of these life forms enter into food webs in the region in the form of...wait for it...detritus! Yup, both fine and course particular organic matter are a main source of these materials. I suppose this explains why heavy accumulations of detritus and algal growth in aquaria go hand in hand, right? Detritus is "fuel" for life forms of many kinds.

In Amazonian blackwater rivers, studies have determined that the aquatic insect abundance is rather low, with most species concentrated in leaf litter and wood debris, which are important habitats. Yet, here's how a food web looks in some blackwater habitats : Studies of blackwater fish assemblages indicated that many fishes feed primarily on burrowing midge larvae (chironomids, aka "Bloodworms" ) which feed mainly with organic matter derived from terrestrial plants!

And of course, allochtonous inputs (food items from outside of the ecosystem), like fruits, seeds, insects, and plant parts, are important food sources to many fishes. Many midwater characins consume fruits and seeds of terrestrial plants, as well as terrestrial insects.

Insects in general are really important to fishes in blackwater ecosystems. In fact, it's been concluded that the the first link in the food web during the flooding of forests is terrestrial arthropods, which provide a highly important primary food for many fishes.

These systems are so intimately tied to the surrounding terrestrial environment. Even the permanent rivers have a strong, very predictable "seasonality", which provides fruits, seeds, and other terrestrial-originated food resources for the fishes which reside in them. It's long been known by ecologists that rivers with predictable annual floods have a higher richness of fish species tied to this elevated rate of food produced by the surrounding forests.

And of course, fungal growths and bacterial biofilms are also extremely valuable as food sources for life forms at many levels, including fishes. The growth of these organisms is powered by...decomposing leaf litter!

Sounds familiar, huh?

So, how does a leaf break down? It's a multi-stage process which helps liberate its constituent compounds for use in the overall ecosystem. And one that is vital to the construction of a food web.

The first step in the process is known as leaching, in which nutrients and organic compounds, such as sugars, potassium, and amino acids dissolve into the water and move into the soil.The next phase is a form of fragmentation, in which various organisms, from termites (in the terrestrial forests) to aquatic insects and shrimps (in the flooded forests) physically break down the leaves into smaller pieces.

As the leaves become more fragmented, they provide more and more surfaces for bacteria and fungi to attach and grow upon, and more feeding opportunities for fishes!

Okay, okay, this is all very cool and hopefully, a bit interesting- but what are the implications for our aquariums? How can we apply lessons from wild aquatic habitats vis a vis food production to our tanks?

This is one of the most interesting aspects of a botanical-style aquarium: We have the opportunity to create an aquatic microcosm which provides not only unique aesthetics- it provides nutrient processing, and to some degree, a self-generating population of creatures with nutritional value for our fishes, on a more-or-less continuous basis.

Incorporating botanical materials in our aquariums for the purpose of creating the foundation for biological activity is the starting point. Leaves, seed pods, twigs and the like are not only "attachment points" for bacterial biofilms and fungal growths to colonize, they are physical location for the sequestration of the resulting detritus, which serves as a food source for many organisms, including our fishes.

Think about it this way: Every botanical, every leaf, every piece of wood, every substrate material that we utilize in our aquariums is a potential component of food production!

The initial setup of your botanical-style aquarium will rather easily accomplish the task of facilitating the growth of said biofilms and fungal growths. There isn't all that much we have to do as aquarists to facilitate this but to simply add these materials to our tanks, and allow the appearance of these organisms to happen.

You could add pure cultures of organisms such as Paramecium, Daphnia, species of copepods (like Cyclops), etc. to help "jump start" the process, and to add that "next trophic level" to your burgeoning food web.

In a perfect world, you'd allow the tank to "run in" for a few weeks, or even months if you could handle it, before adding your fishes- to really let these organisms establish themselves. And regardless of how you allow the "biome" of your tank to establish itself, don't go crazy "editing" the process by fanatically removing every trace of detritus or fragmented botanicals.

"Project 18" was a tank which really pushed this idea to the forefront of my daily practice. Everything from the selection of materials to the way the tank was set up, to the "aquascape" was imagined as a sort of "whole."

Yeah, I said the "A" word...Let's think about the "aquascape" part bit more deeply for just a second...

What IS the purpose of an aquascape in the aquarium...besides aesthetics? Well, it's to provide fishes with a comfortable environment that makes them feel "at home", right?

Exactly...

So when was the last time you really looked into where your fishes live- or should I say, "how they live" - in the habitats from which they come? The information that you can garner from such observations and research is amazing!

One of the key takeaways that you can make is that many freshwater fishes like "structure" in their habitats. Unless you're talking about large, ocean going fishes, or fishes that live in enormous schools, like herring or smelt- fishes like certain types of structure- be it rocks, wood, roots, etc.

Structure provides a lot of things- namely protection, shade, food, and spawning/nesting areas.

And of course, the structure that we are talking about in our aquairums is not just rocks and wood...it's all sorts of botanical materials and leaves that create "microhabitats" in all sorts of places within the aquarium.

We can utilize all of these things to facilitate more natural behaviors from our fishes.

So, yeah-think about how fishes act in Nature.

They tend to be attracted to areas where food supplies are relatively abundant, requiring little expenditure of energy in order to satisfy their nutritional needs. Insects, crustaceans, and yeah- tiny fishes- tend to congregate and live around floating plants, masses of algae, and fallen botanical items (seed pods, leaves, etc.), so it's only natural that our subject fishes would be attracted to these areas...

I mean, who wouldn't want to have easy access to the "buffet line", right?

And with the ability to provide live foods such as small insects (I'm thinking wingless fruit flies and ants)- and to potentially "cultivate" some worms (Bloodworms, for sure) "in situ"- there are lots of compelling possibilities for creating really comfortable, natural-appearing (and functioning) biotope/biotype aquariums for fishes.

Ever the philosopher/ muser of the art of aquaristics, I sometimes fear that the burgeoning interest in biotope aquariums at a contest level will result in the same sort of "diorama effect" we've seen in planted aquarium contests. In other words, just focusing on the "look" (which is cool, don't get me wrong) yet summarily overlooking the reason why the habitat looks the way it does and how fishes have adapted to it...and considering how we can utilize this for their husbandry, spawning, etc.

I'm sure it's unfounded, but the so-called "nature aquarium" movement seems to have, IMHO, completely overlooked the real function of nature, so there is some precedent, unfortunately. I hope that "biotopers", who have a lot of awareness about the habitats they are inspired by, will at least consider this "functional/aesthetic" dynamic that we obsess over when they conceive and execute their work.

It should go beyond merely creating the "look" of these systems to win a contest, IMHO. Rather, we should also focus on the structural/functional aspects of these environments to create long-term benefits for the fishes we keep in them. That's a real "biotope aquarium" in my book.

Leaves, detritus, submerged terrestrial plants- all have their place in an aquarium designed to mimic these unique aquatic habitats. You can and should be able to manage nutrients and the bioload input released into our closed systems by these materials, as we've discussed (and executed/demostrated) here for years. The fear about "detritus" and such "crashing tanks" is largely overstated, IMHO- especially with competent aquarium husbandry and proper outfitting of a tank with good filtration and nutrient control/export systems in place.

If you're up to the challenge of attempting to replicate the look of some natural habitat- you should be a competent enough aquarist to be able to responsibly manage the system over the long term, as well.

Ouch, right? Hey, that's reality. Sorry to be so frank. Enough of the "shallow mimicry" B.S. that has dominated the aquascaping/contest world for too long, IMHO. You want to influence/educate people and inspire them? Want to really advance the hobby and art/science of aquarium keeping? Then execute a tank which can be managed over the long haul. Crack the code. Figure out the technique. Look to Nature and "back engineer" it.

These things can be done.

There are many aspects of wild habitats that we choose to replicate, which we can turn into "functionally aesthetic" aquarium systems. Let's not forget the trees themselves- in their submerged and even fallen state! These are more than just "hardscape" to those of us who are into the functional aesthetic aspects of our aquariums.

I hope that you have your own "Project 18"- an aquarium which served as an "unlock" for the future of your botanical method work. I hope that you find your unique way in the hobby, and enjoy every second of it!

Stay bold. Stay creative. Stay observant. Stay thoughtful...

And Stay Wet.

Scott Fellman

Tannin Aquatics

A Steady Diet of...

I think that one of the most interesting- and perhaps, not widely overlooked aspects of botanical method aquariums is their ability to provide sustenance for the fishes which reside in them. Yeah, we DO talk a lot about how to feed our fishes, and how best to provide nutrition for them in thenmhobby. However, have you ever thought of how it might be possible to create an interesting fish community and display based on the different feeding strategies of fishes?

In other words, constructing your aquarium with the expressed purpose of supporting the various feeding adaptations of different fishes!

The idea is absolutely not crazy, nor "revolutionary"- but it is something...an "angle", if you will- that we should be considering when we construct our aquariums.

One of the most important functions of many botanically-influenced wild habitats is the creation and support of food webs. As we've discussed before in this blog, the leaf litter zones in tropical waters are home to a remarkable diversity of life, ranging from microbial to fungal, as well as crustaceans and insects...oh, and fishes, too! These life forms are the basis of complex and dynamic food webs, which are one key to the productivity of these habitats.

By researching, developing, and managing our own botanically-influenced aquaria, particularly those with leaf litter beds, we may be on the cusp of finding new ways to create "nurseries" for the rearing of many fishes!

At least upon superficial examination, our aquarium leaf litter/botanical beds seem to function much like their wild counterparts, creating an extremely rich "microhabitat" within our aquariums. And reports form those of you who breed and rear fishes in your intentionally "botanically-stocked" aquariums are that you're seeing great color, more regularity in spawns, and higher survival rates from some species.

We're just beginning here, but the future is wild open for huge hobby-level contributions that can lead to some serious breakthroughs!

Nature has been providing for the organisms which live in Her waters for eons...So I think any discussion about possible food production in a botanical method aquarium starts there...

The population and distribution of the fishes is based partially upon what food resources are available in a given locale.

A typical tropical stream or river has a variety of different feeders, each one specializing in a different method of feeding.

You'll often hear the term "periphyton" mentioned in a similar context, and I think that, for our purposes, we can essentially consider it in the same manner as we do "epiphytic matter." "Periphyton" to the hobbyist is essentially a "catch all" term for a mixture of cyanobacteria, algae, various microbes, and of course- detritus, which is found attached or in extremely close proximity to various submerged surfaces.

Again, fishes will graze on this stuff constantly.

In fact, many of our favorite fishes may be classified as "periphyton" grazers, which have small mouths, fleshy lips, and numerous tiny teeth for rasping. "Periphyton", by the way, is defined by science as "...freshwater organisms attached to or clinging to plants and other objects projecting above the bottom sediments." Ohh- sounds good to me! This stuff is abundant in all sorts of streams, but can be limited by availability of light and solid substrates.

It's noteworthy to point out that detritus is a less nutritious resource for grazers than the typical periphyton, especially for fishes like loricariid catfishes and such- and is thought by scientists to only be actively consumed when the periphyton growth is limited. So, interestingly, fishes do shift their feeding patterns to adapt to seasonal and other changes in their habitat..something we can replicate in our aquariums, no doubt!

Natural aquatic habitats can range from highly productive to relatively impoverished.

Major rivers like the Rio Negro are often called "impoverished" by scientists, in terms of plankton production. They also show little seasonal fluctuations in algal and bacterial populations. Other blackwater systems do show seasonal fluctuations, such as lakes and watercourses enriched with overflow in spring months.

At low water levels, the nutrients and population of these life forms are generally more dense. Creatures like hydracarines (mites), insects, like chironomids (hello, blood worms!), and copepods, like Daphnia, are the dominant fauna that fishes tend to feed on in these waters. This is interesting to contemplate when we consider what to feed our fishes in aquariums, isn't it? Hmm...Why don't more commercial fish foods contain mostly aquatic insects? Hint, hint, hint, hint...

Anyways, these life forms, both planktonic and insect, tend to feed off of the leaf litter itself, as well as fungi and bacteria present in them as they decompose. The leaf litter bed is a surprisingly dynamic, and one might even say "rich" little benthic biotope, contained within the otherwise "impoverished" waters. And, as we've discussed before, it should come as no surprise that a large and surprisingly diverse assemblage of fishes make their homes within and closely adjacent to, these litter beds. These are little "food oasis" in areas otherwise relatively devoid of food. The fishes are not there just to look at the pretty leaves.